Background

After completing a masters degree in philosophy I faced a difficult decision. I could not imagine myself remaining cloistered in a university environment – I wanted to be out there in the real world; at the ‘coal face’ dealing with hard-edged problems.

After training as a clinical psychologist I worked with mental health services in West Auckland, alcohol and drug services in South Auckland, violence programmes on the North Shore, and eventually set up my own practice. These diverse practice contexts gave me an in-depth appreciation of the issues affecting people’s wellbeing, including family breakups, violence and abuse, addictions, mental health challenges, bereavements and existential suffering. My stance on the ‘real world’ began to alter. I could see how many of the approaches to psychological practice were driven more by unthinking traditions than well-thought-out strategies. I started to appreciate how research and teaching play a vital role in what happens in the ‘real world’.

After completing a PhD in psychology in 1991, I took up an academic position. Ever since I have devoted much of my time to teaching with a focus on applied practice. I derive particular satisfaction at the way my teaching, research supervision and curriculum design has contributed to improved responses to societal issues such as addictions and violence. Over time I can see how my efforts have helped create a better educated workforce both for those working in medical roles, and for addiction and mental health specialists.

My journey from practitioner to teacher was informed by one key challenge: how to engage students and practitioners, and get them to challenge assumptions and think differently about what they are doing.

Learning Environment

Many of those enrolling in the Postgraduate Certificate in Alcohol and Drugs are adult practitioners who have not studied for many years and feel intimidated by the university systems. I work hard with these students to de-mythologize what they see as a large, impersonal and mysterious institution. I do this through a combination of making myself very approachable, carefully explaining the systems for assessment and providing considerable feedback on ways to improve on assignments.

Once a sense of safety is achieved, students are then more open to having their previous assumptions challenged. In my classes on theory I openly announce my intention to shake up previous understandings. I warn students that this can generate uncertainty and anxiety but, at the same time, in a safe environment they capable of exploring these new territories.

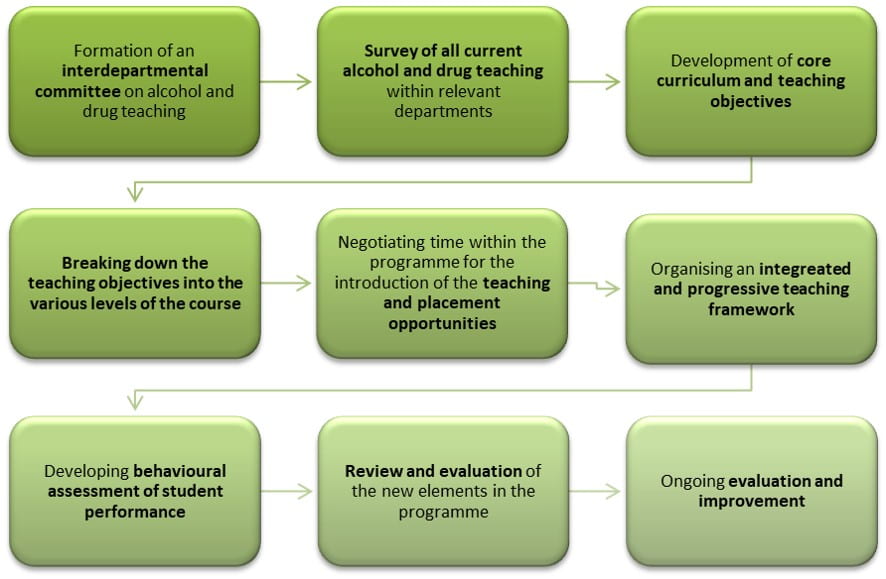

Curriculum Design

Effective teaching of approaches to clinical issues as relies heavily on careful construction of a learning framework. My efforts in teaching have focused on improving curriculum design and seeking to avoid the many pitfalls that can block learning, such as a curriculum over-burdened with teaching content, where students become swamped and lose sight of the primary learning objectives.

Learning objectives play a crucial role in deciding on teaching methods, content and assessment processes. This calls for a constant dialogue between the overall objectives and the objectives used in each component of the programme. These objectives were then used in formulating course/module learning objectives and for guiding decisions on appropriate course structure and assessment processes. I took particular care in ensuring each module (or course) which comprised the programme, referenced and interfaced with the learning objectives for the whole programme to facilitate alignment of graduate outcomes with what the violence intervention workforce was requiring.

COURSES DEVELOPED

| Course Number | Title | Years Taught | Typical Numbers | Role |

| POPLHLTH 700 | Community Health Development | 2019 onwards | 6-15 | Co-developed, coordinated & co-teach course |

| POPLHLTH 774 | Addictive consumptions & public health | 2017 onwards | 10-20 | Developed, coordinated and teach whole course |

| POPLHLTH 737 | Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Studies | 1998

onwards |

35-45 | Developed, coordinated and teach whole course. |

| POPLHLTH 758 | Theoretical concepts of health | 2009

onwards |

14-21 | Developed, coordinated and taught whole course. Compulsory paper for postgraduate honours programme |

| POPLHLTH 712 | Effective interventions for lifestyle change | 1998-

2009 |

15-25 | Developed, coordinated and taught whole course. Uses innovative group teaching. |

| POPLPRAC 709 | Gambling and health | 2002-

2016 |

6-8 | Developed, coordinated and taught whole course (offered every second year) |

| POPLPRAC 708 | Assessment and intervention | 1998–

2000 |

20 | Core whole year (30-point) course for alcohol and drug PGCert. Developed, coordinated and taught whole course |

| BEHAVSCI 721 | Alcohol, tobacco and other drugs | 1995-

1997 |

10 | Whole year (30 point) course designed for masters students. Developed, coordinated and taught whole course. |

PROGRAMMES DEVELOPED

|

|

Initiated | Co-ini-tiated | Co-de- signed | Imple- mented | Notes |

| Masters of Health Practice | 2015 | 2016 | 2018 | Designed Faculty degree and took it through University and CUAP approvals | |

| Post-graduate programmes in Alcohol and Drug Studies |

1997 |

1997 |

1997

onwards |

Designed and taught Certificate, diploma and masters programme | |

| Post-graduate programme in Mental Health Development | 2000 | 2001 | 2001 | Initiated idea and supported development of on-going programme and engaged 2 years of MOH funding | |

| Post-graduate programme on opioid dependency | 1999 | 1999 | 1999-

2002 |

Designed and oversaw programme for 3 years for primary health care professionals | |

| Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs (TADS) Project | 1995 | 1995 | 1996-

2006 |

Oversaw & chaired management group for this primary health training in brief intervention. | |

| Diploma of Violence and Trauma Studies (AUT University) | 1992 | 1993 | Initiated and designed this AUT undergraduate programme in violence intervention. Still being taught. | ||

| Alcohol and Drug teaching in medical programme | 1992 | 1992 | 1993

onwards |

Coordinated coherent teaching through all five years of the programme | |

| Communication teaching in medical programme | 1991 | 1991 | 1997–

1998 |

Co-developed and implemented communication teaching |

TEACHING PUBLICATIONS

Adams, P.J., Sellman, D., Newcombe, D., Adamson, S., White, S., Deering,D., Todd, F. Postgraduate alcohol and other drug practitioner training in New Zealand: Significant influences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(3), 468-474. Read more

Adams, PJ and Buetow, S. (2014) The Place of theory in assembling the central argument for a thesis or dissertation. Theory and Psychology, 24(1) 93-110.

Newcombe, D.A.L., Adams, P.J. (2009) ‘Vocational vs Academic agendas in Post Graduate AOD Teaching: What is the right balance?’, Australasian Professional Society on Alcohol and Other Drugs 2009, Darwin, Australia, November 1 – 4.

Adams, P. (2003). The Wizard of Oz and the new alcohol and drug professional. In A. Roche and J. McDonald (eds.) Catching Clouds: Exploring Diversity in Workforce Development in the Alcohol and Other Drug Field: p193-200. Adelaide: National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction.

Cape G. Ivory S. J. Robinson G. Sellman D. Adams P. (2001) Evaluation of Alcohol and Drug Education and Training in New Zealand. A report prepared for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand, 44pp.

Adams, P. (1999) The use of project proposals in a post-graduate programme for drug and alcohol service workers. Presented at the Australasian Symposium on Professional Education and Training on Alcohol and Other Drugs, Adelaide, Australia.

Adams, P.J. (1995) Update on development in alcohol and drug teaching at the Auckland School of Medicine. Presented at the annual meeting of Australasian alcohol and drug coordinators in medical schools, Melbourne Australia, May 1995.

Links

- Study options School of Population Health, University of Auckland

- Learning Teaching Unit, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland

- School of Graduate Studies, the University of Auckland

- Addiction studies, School of Population Health, University of Auckland